The number four slot in my top ten characters list goes to the third of the regicides to flee to America, where despite his wanted status he was able to live openly under an assumed name.

4: John Dixwell (1607 – 1689)

‘The King will not rest until we are all on the scaffolds of Tyburn, hanged, drawn and quartered in his vengeful retribution.’”

John Dixwell, Puritan, Chapter Five

Unlike Edward Whalley and William Goffe, whom we met in number seven of this series, fellow regicide John Dixwell was not an ardent Puritan seized by the zeal of religious calling. Instead his motivation was political, driven by a fervent belief in the republican cause. Born to a well-off Warwickshire family (there is a family monument in the church at Churchover, near Rugby), he was later raised by his uncle in Kent where he inherited custody of a large estate after the death of his elder brother. Subsequently trained as a lawyer at Lincoln’s Inn, when civil war came Dixwell served on the Kent Committee of Sequestrations – responsible for the seizure of Royalist estates – and as a captain in the Kent militia before becoming MP for Dover in 1646.

Servant of the Republican State

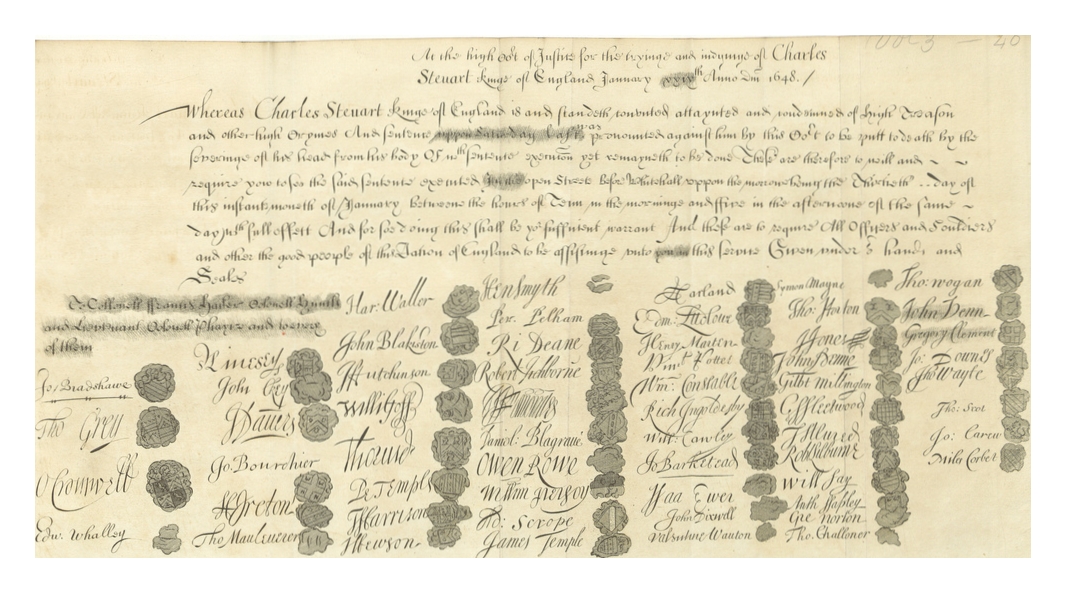

Once in Parliament, Dixwell was part of the radical Independent faction supported by Oliver Cromwell, and as such he survived the Army’s purge of Parliament at the end of the civil war that removed those MPs who were in favour of negotiating with the captured Charles I. The vastly trimmed so-called Rump Parliament of around eighty MPs quickly set up a High Court of Justice to put the King on trial. Dixwell attended every session and was one of the 59 judges who signed the King’s death warrant, making him in later years one of the infamous regicides whom the King’s sons hunted with unforgiving hunger. After the King’s execution, the Rump Parliament, now including some former MPs who had been against that fatal act, moved to abolish the House of Lords and the monarchy by declaring England a republic, ultimately bringing Scotland and Ireland into the new Commonwealth as well.

During the 1650s, Dixwell served variously as a member of Cromwell’s Council of State, Member of Parliament, and Governor of Dover Castle. When the Rump Parliament was dissolved in 1653, he was against the creation of the Protectorate which saw huge powers awarded to a King-like Lord Protector, but nonetheless served in all three Parliaments under Protector-for-life Cromwell and then his son Richard Cromwell, in whose Council of State he also served. After Richard’s quick fall from power, Dixwell held Dover Castle for the civilian republican faction when conflict with the Army threatened, until to avoid further descent into chaos the exiled son of the King was invited to return to the throne in 1660 as King Charles II.

Escape to America

Seeking to bring healing to a nation torn apart, the new King ordered an Act of Oblivion granting general amnesty to his Parliamentarian opponents, with one glaring exception: the regicides. To those men who had signed his father’s death warrant he showed no mercy, commanding they be arrested, tried and in many cases executed. To avoid arrest, Dixwell used the excuse of illness to ask for more time to give himself up, but in reality he was in perfect health, and he used the time he was naively given to sell off much of his estate before fleeing to the continent, no doubt to the fury of the King.

So well did Dixwell hide in his exile that he essentially disappears from the record for the next five years, until he finally resurfaced in America in early 1665. In my novels, I use those missing years to contend that he had sailed to New Amsterdam in Dutch America until it was captured by the British fleet in 1664 and renamed New York. In my fiction, it is here that he appears in Birthright as the mysterious Englishman who somehow knows of Mercia’s past and who helps her evade a lynching at the hands of the Dutch.

A New Identity

After taking New Amsterdam, the fleet under the command of Richard Nicolls (see number nine in this series) was tasked with seeking out those regicides who were known to have fled to America, meaning Edward Whalley and William Goffe. By 1665, as per the events of Puritan, Whalley and Goffe were hiding away in Hadley, and Dixwell must have known this for Hadley is where he returns to the historical record in February of that year (in Puritan, I have him accompanying Whalley and Goffe on their journey north). But unlike his less careful associates, none of his enemies knew Dixwell was in America. More or less, his freedom remained his.

Under his assumed name of James Davids, Dixwell decided to move to New Haven, a coastal town strongly resistant to British interference that had initially been the centre of a separate colony, but which was now being absorbed into Connecticut. Here he set up a new life as a visible, if necessarily reclusive, part of the community. No doubt some of his new neighbours were aware of his true identity, but for the most part his past remained hidden, although relatives back in England would occasionally send him money and goods.

Twice Remarried

Soon after arriving in New Haven, Dixwell/Davids moved into the home of an elderly couple, Benjamin and Joanna Ling. When Benjamin died in 1673, Dixwell married Joanna, who herself passed away within a month of the marriage. Presumably Dixwell inherited the Ling house, and then in 1677, at the age of seventy, he married again, this time to a much younger woman by the name of Bathsheba How. Despite his advanced age, the couple went on to have three children: Mary, John and Elizabeth Davids.

In his final years, Dixwell made attempts to secure the estate he had left behind in England for his children, and even held out hopes of returning himself. By 1688 Charles II was dead, and his brother and successor James II had been removed from the throne in the so-called Glorious Revolution. With both the sons of Charles I gone, there was a glimmer of hope that any remaining regicides in exile might be allowed home. But for Dixwell it was not to be. Now in his eighties, he died mere months later in New Haven in March 1689, having evaded capture until his end. At last the truth of his past could be revealed, and his descendents were free to take the name of Dixwell for their own.

Next: King Charles II: exiled Prince, restored King

Photograph by Matthew Jackson

The images of Charles I’s death warrant and the plan of New Haven come via the British Library Mechanical Curator service that has given access to over one million images of out-of-copyright material