The next real-life character we examine in my historical blog series is the stubborn last Governor of Dutch New Amsterdam: war hero to some, authoritarian despot to many.

5: Pieter Stuyvesant (1610 – 1672)

‘Why should I surrender? This place was a hovel when I arrived, a den of prostitutes and thieves. It was nothing. I have made it succeed.’”

Pieter Stuyvesant, Birthright, Chapter Thirty

Of all the real-life characters in the Mercia Blakewood novels, Pieter Stuyvesant is the one I knew least about before I started to write, but my research threw up a fascinating story of a man with intense self-belief – and overwhelming self-conceit. He has a minor role in Mercia’s adventures, questioning her briefly when she is captured in New Amsterdam, but his role in history is significant, for it was Stuyvesant who took a small trading post at the mouth of the River Hudson and turned it into a thriving settlement that would become the modern metropolis of New York. But it is also Stuyvesant who lost that settlement for the Dutch, in part through his unpopular domineering approach to his leadership.

Born in the rural Netherlands, Stuyvesant’s life started plainly enough, but soon began to take on a more dramatic flair when he was expelled from university for allegedly seducing his landlord’s daughter. Undaunted, as was his character, he moved to the bright canalside lights of Amsterdam to join the West India Company (WIC), the world’s foremost trading concern, and from there he began his foreign career. Serving first in Brazil, his tenacious work ethic saw him quickly ascend through the ranks. He was rewarded with a posting to the Dutch colony of Curacao in the southern Caribbean, where he distinguished himself sufficiently to rise to the role of Governor and commander of strategy in the wider Caribbean while still barely into his thirties.

Appointed by God

In 1644, Stuyvesant led an attempt to retake the Spanish-controlled island of St Martin for the Dutch. At the head of a substantial fleet with hundreds of troops, he put the island to a protracted siege, but during a ground assault his right leg was blown to pieces and had to be amputated at the knee. Soon afterwards the siege was lifted, and returning to Amsterdam to recover, it was here that he first put on his wooden prosthesis, the peg leg he became famous for wearing. Rather than dissuading him, the experience gave him renewed vigour, and only one year later the WIC appointed him to take charge of the ailing New Netherland colony on the eastern American coast: indeed so sure of himself was Stuyvesant that he believed he had been assigned to turn the colony’s fortunes around by God. During his convalescence, he met and married his wife Judith, and in 1647 the couple set off for the colony’s principal settlement, New Amsterdam.

Seeing for himself how the rundown colony had festered under the previous governor, Stuyvesant became seized with the zeal of an evangelist to put things to rights. He reportedly told the colonists he would treat them as a father would treat his children, but it quickly became clear that his approach to parenting was more disciplinarian than indulgent. Alienating the wealthy patroons (landowners) and ordinary citizens alike, Stuyvesant’s heavy-handed authoritarianism soon made him unloved. While he allowed the population to elect a council of advisors, he ensured the council had no real power and retained the final say on all matters for himself. When the council objected to his proposals for agreeing a border with New England, he threatened to dissolve it; whenever a deputation of colonists demanded reforms, he regularly dismissed them out of hand. But the military discipline he brought to bear on the colony did succeed in improving its economy and trade. Defences were also enhanced, with the erection of a wooden wall or palisade at the north side of town, running along the line of modern Wall Street. Occasionally, he would take the advice of senior members of the community but attempts to soften his style of rule invariably met with failure.

Remonstrance and Defeat

In particular, Stuyvesant was not one to tolerate anything he disapproved of. Most notably, he attempted to stymie religious freedom among groups such as Lutherans and Quakers, despite the broader more tolerant Dutch position on freedom of conscience. When he put a young Quaker preacher to torture, and made it illegal to give shelter to Quakers, this led to residents of the town of Vlissingen (Flushing) compiling what is known as the Flushing Remonstrance in protest. Stuyvesant responded by arresting and even imprisoning those authors of the Remonstrance who did not recant their words, but the document is now considered one of the most important early colonial period writings and viewed as a precursor to the provisions on religious freedom in the US Bill of Rights.

Then in 1664 Charles II dispatched a fleet across the Atlantic to seize New Netherland and New Amsterdam for the British. As seen in Birthright, the fleet led by Colonel Richard Nicolls (see number 9 in this series) sailed into the harbour and sent a letter demanding Stuyvesant surrender the colony. Ever stubborn even at this juncture, Stuyvesant’s response was to send the letter back because it was unsigned. Once this oversight had been corrected, he refused point blank to surrender, leading to the scene in Birthright where Mercia eavesdrops on his council meeting, watching as the councillors demand to see the terms of surrender only for Stuyvesant to instead rip them up. Well aware of the masses of waiting British troops, the townsfolk subsequently turned on Stuyvesant and forced him to capitulate. And so the proud man had no choice but to march from his seat to hand the town to the British in much the way described in Birthright, helpless to hold back history as New Amsterdam became New York.

The Dutch Legacy

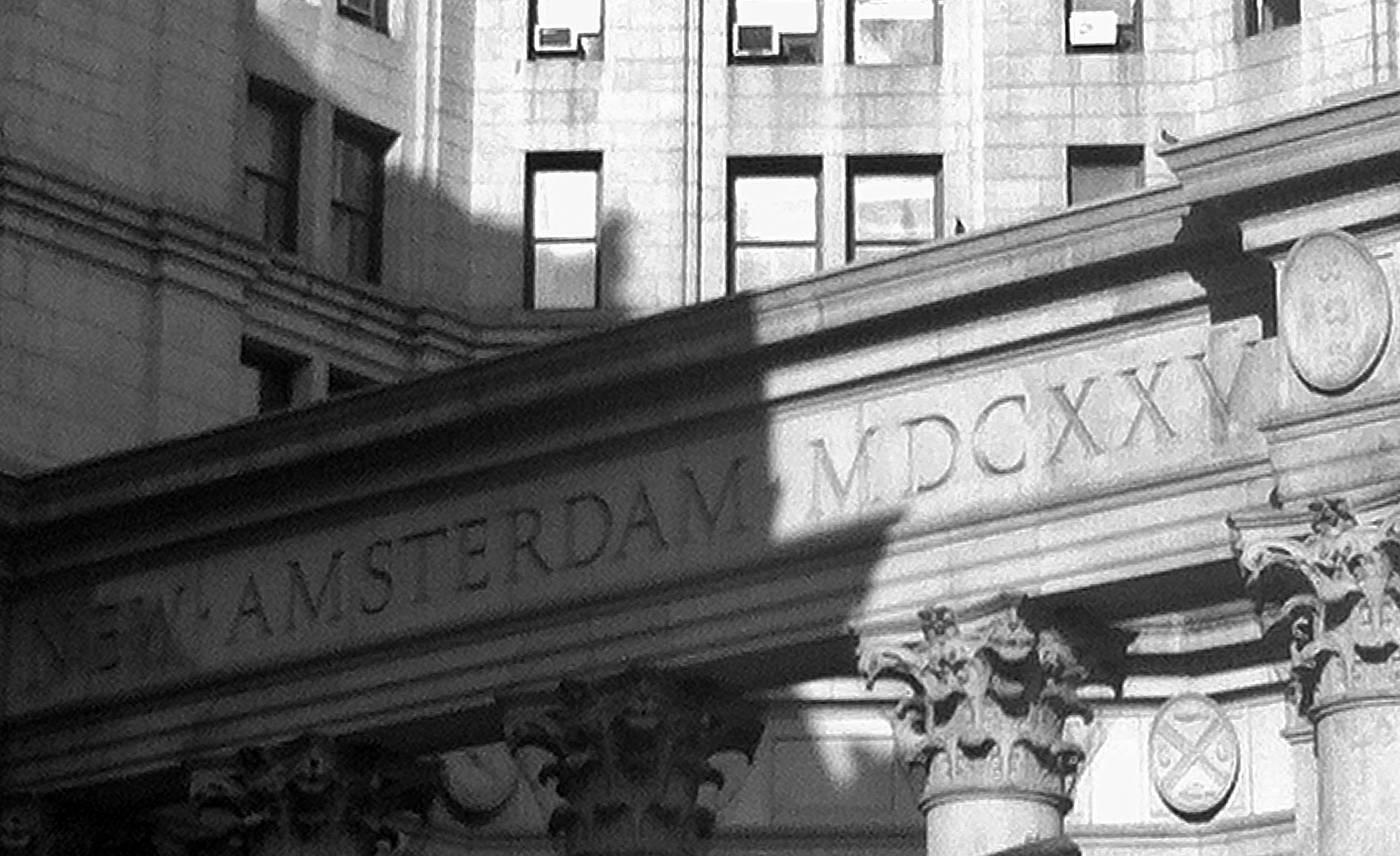

After his humiliation, Stuyvesant was summoned back to Amsterdam to explain himself, but he subsequently returned to New York to take up residence at his farm, or bouwerij, living as a citizen in the town he had once governed absolutely until his death there in 1672. He was buried in his family chapel, where St Mark’s Church now stands on the corner of Second Avenue and, appropriately, Stuyvesant Street. Downtown New York is full of such reminders of Stuyvesant’s legacy, most notably in the area around his bouwerij – the modern Bowery – home to such places as Stuyvesant Square and Stuyvesant Town, a nearby apartment complex. Wider Dutch influences are apparent throughout New York, for example in the names of Brooklyn (Breuckelen), Harlem (Haarlem) and Staten Island, and in such American terms as cookie (koeckje) and boss (baas). Pieter Stuyvesant’s memory still lingers in his adopted home, if you look.

Next: John Dixwell, aka James Davids, the regicide who changed his identity to live openly in New World exile

Photographs by Matthew Jackson / David Hingley